The Advertiser's Dilemma and the Curse of Lagging Cultural Relevance

There’s a common trope in marketing land today: “Consumers hate ads and will avoid them at all costs.” Advertisers have moved from producing ads to making ‘content’. The term advertising has ironically developed a sour taste for ad agencies and brands tasked with producing them.

The truth is more nuanced. Yes, consumers hate most ads but that is because most advertising is bad. People respond well and take action in response to great advertising. Yet, that begs the question - why are so many ads bad and what constitutes ‘bad’ in this advertisers opinion?

A bad ad is one that doesn’t sell. The short of why this happens is fear. The longer answer lies in a network of underlying incentives that dominate contemporary marketing suites, discourage brave messaging, and reward mediocrity. Those incentives result in a glut of terrible ads from the Fortune 500 brands that we see every day.

The Advertiser’s Dilemma: Why Most Big Brand Advertising Communication Feels Inauthentic and Boring

David Ogilvy

“Advertising is not an art form. It’s a medium for information, a message for a single purpose: to sell.

Advertising’s main goal is to make you do something. Download this app, swipe your credit card, take out a loan, try this restaurant, don’t litter, wear your seat belt, buy this suit. An ad represents a specific form of communication with a singular goal - influencing a consumer’s decision to spend money with your business. As David Ogilvy famously put it, “Advertising is not an art form, it’s a medium for information, a message for a single purpose: to sell.”

That is very different from entertainment, a medium that has the express purpose of evoking emotion. Advertising can and should evoke emotion but do so in the service of influencing a buying decision for a product or service. What we have today is the worst of both worlds, advertising that is both hard to watch, evokes little empathy in a consumer, and fails to move consumers to purchase. A sea of advertisements that fail to capture your attention, convey meaning, inform, or encourage commerce.

Modern advertising, especially from large, established brands rarely makes you think, arrests your attention, or challenges your perceptions. This is due to a number of conflicting incentives large brands face in producing interesting communications. Namely, a large brand’s main objective is to retain market share rather than gain it. This puts fringe communication strategies, many of which are more interesting, provoking, or new, outside the realm of possibilities a larger brand will entertain. When you own the majority of your market, your appetite for risk decreases because the negative consequences of alienating consumers outweigh the benefits of gaining one.

“Large brands, incentivized to maintain brand equity and market share, will necessarily favor safe communication strategies while discouraging novel ones.”

This is what I call the Advertiser’s Dilemma: large brands, incentivized to maintain brand equity and market share, will necessarily favor safe communication strategies while discouraging novel ones. This applies to both creative and media. When your existing customer base is a majority of a population, you must appeal to the broadest possible audience. Broad audience appeal usually results in bland, palatable, and pandering communication strategies. In America, where the same 10 companies own 40-50% of every industry’s market share, the Advertiser’s Dilemma has produced a glut of mediocre, boring advertisements that accost us at every turn.

The Curse of Lagging Cultural Relevance

Snippet of the thousands of pride logos displayed this past June.

Faced with the Advertiser’s Dilemma, large brands will gravitate towards safe messaging bets. A safe messaging bet is one that consumers have seen or agree with already. Empirically, this looks like brands leaning into topics, themes, and celebrities that have already been accepted in the cultural zeitgeist. A great example of the dilemma’s correlation with cultural irrelevance is the deluge of rainbow pride logos that suddenly appear every June. LGBTQ branded logos were almost non-existent prior to 2000. They slowly grew in popularity between 2009-2016 during the Obama years, the first administration that formally endorsed same-sex marriage, and became almost inescapable this June after the Biden administration formally codified June as Pride Month.

Pride logos no longer stand out or make a statement. That is because the vast majority of Americans have gotten on board with LGBTQ rights. Once Pride crossed into the mainstream, brands opportunistically jumped on board. These brand communications are lagging indicators of a cultural norm that has already occurred. Once most people agree, brands capitalize. The worst offending companies have even been labeled ‘rainbow capitalists’ for the practice of slapping pride colors on whatever merchandise they hock to consumers.

Authentically taking a stand is hard, but pays dividends. In 2013, Cheerios ran an ad featuring a mixed-raced family which drew a slew of racist comments and rants online. Some messages were so appalling that General Mills disabled the comment section on their YouTube video. The ad, in terms of marketing return, was a massive success due to the conversation it generated. Cheerios received weeks of coverage across all major news outlets far beyond its initial media spend. The President of Deutsch responded to the contraversy and success of the ad, “What’s unfortunate is that I still think 97 percent of companies would stay away from this because they would say, ‘I don’t need the letters.’” This is a brand being incredibly culturally relevant.

When most brands favor generally accepted, palatable comms, they sound like everyone else. These brands become victims of their own fear, following consumer trends rather than setting them. The Advertiser’s Dilemma causes brands to lag behind popular culture, tied to boring advertising strategies that don’t differentiate their products, grow brands, or drive sales. This is the state of most brand marketing today and the slog of skippable ads you see across screens every day. Add legal precaution and massive holding company bureaucracy to the fear of alienating market dominant positions, and you’ve brewed a poignant pesticide against innovative ideas.

This is the Curse of Lagging Cultural Relevance. Brands become lagging indicators of culture rather than drivers of it. Faced with the Advertiser’s Dilemma, brands favor safe messaging bets that are generally accepted by society. Those safe messaging bets make the brand’s communications lag behind the cultural conversation and risk brand irrelevance.

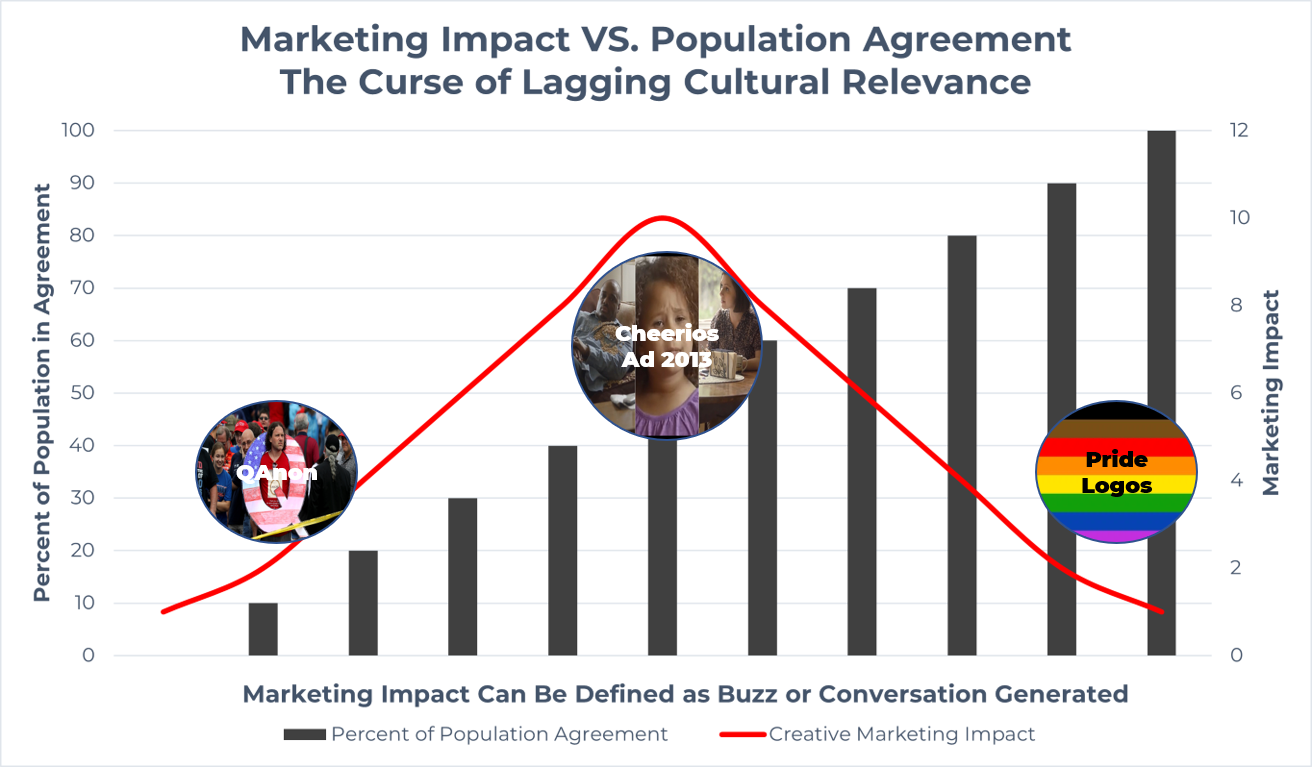

You can visualize the marketing impact of a cultural relevant communication strategy against the agreement or congruity of a population in the chart below. The marketing impact, which can be defined as buzz or conversation generation is scaled 1-10. The graph of marketing impact forms a bell curve depending on where the population’s sentiments lie on any particular topic.

At the low end of population congruity/agreement, market impact will be low because very little of a population agrees with the marketing communications. QAnon theories fit this description. They receive some traction within their bubbles but generally don’t spark conversation outside their community (mostly because they are stupid and disconnected from reality but that’s another post).

On the other end of the spectrum we have topics, themes, or designs that the vast majority of the population is familiar or agrees with. Today, Pride logos represent this as they generate very little friction in the USA population psyche. With general acceptance at high levels, a pride logo slapped on merch or a logo does not generate much impact. It doesn’t mean brands can’t play in this area if they authentically support the community, but they should not expect it to generate conversation or buzz.

The center of this chart generates the most impact with the highest level of conversation generation and buzz as a result of marketing communications. Think Cheerios interracial family ad cerca 2013, a Pride logo cerca 2009, Colin Kaepernick and Nike’s ad cerca 2019, or extremely innovative or provocative ads like the Squatty Potty’s Unicorn Poop Ad. When half of the population agrees and the other half doesn’t, expect discord to ensure. This discord is what generates conversation and moves society forward as one segment of the population shifts opinion to one side or the other.

Today those issues are mainstream, but new ones arise every day. Most brands play on the right side of the graph, churning out bland communications that everyone has seen before. The topics causing immense discord in the U.S. population today are abortion rights, gun ownership, immigration, and new design aesthetics like street graffiti moving into the art world. Does your brand dare to wade into the fray? Can your brand capitalize on the conversations of the day by making a bold statement in one direction or another? Is your brand brave enough to try something new?

These questions deserve further study. In our second installment exploring The Advertiser’s Dilemma and population congruity, we will analyze why challenger brands have a unique opportunity to capitalize on discordant topics. We will also look at how larger brands can fight their market size incentive structures to produce more impactful communication strategies.